Global Warming, Obesity, China, Stephen Hawking, and Imagination

|

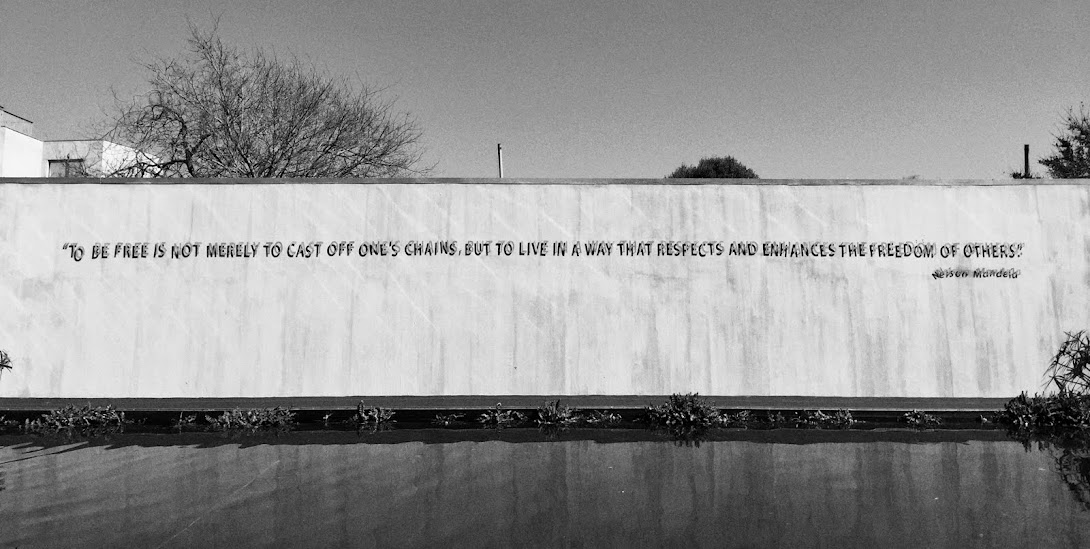

| Continuing on with the theme of randomness: a random picture of my shelf overladen with National Geographic magazines. |

A disclaimer/sorry excuse for the sparseness of posts: much of my time at the moment is drowned by my focus upon English coursework and its associated texts/further reading, revision for impending tests, and training. My pace of reading is consequently much slower than usual. I am (was) however currently catching up on National Geographic magazines (hence the otherwise largely incongruous picture) and reading 'Geopolitics - A short introduction'. My blogger account has nevertheless become saturated with drafts of half-started, half-finished, largely-incomprehensible posts regarding a range of random points. Rather than discard them entirely, I thought of compiling a post of mini-posts. And thus was born this random conglomeration of thoughts.

Thought #1: Global Warming

Cue sigh.

I know, it's a topic over-exhausted beyond belief, but that's only because of its importance. Anyway, this has nothing to do with it in that facet, but rather in terms of its constituents and validated nature. Making my revision notes for AS earlier this year and GCSE last year (both Geography), I was always a bit hesitant as to which section I'd put Global Warming under - human or physical. Is it a physical phenomenon? Or a human phenomenon? If you were to Google it, you'd get more hits under physical Geography. But then, isn't it a human impact upon the environment thereby making it a human phenomenon? Are we not largely responsible for it? But, then again, it is all to do with environmental quality and processes, so surely it's physical? And hence arises the tension between classificatory schemes of Geography.

Global Warming is exemplar in illustrating the inter-relatedness of Geography; I think it more both than one or the other. It is undeniably of human concern regarding both its causes, effects and future, just as it is undeniably physical in explicit nature and immediate implication. It has been interesting to follow the stance of articles such as

this in the news over the past few months, watching the juxtaposing importance placed by different journalists on physical or human elements. To restore a more harmonious dynamic of our relationship, both sides of the relationship need addressing; yes, address fuels and the release of damaging components etc., but also address attitudes, understanding and ability to act on different levels (local, national, international etc.).

Thought #2: Obesity

Obesity + (type 2) diabetes = strictly first world problems of affluence and excess. Right?

Wrong.

With all the current publicity surrounding methods of tackling the UK's growing obesity problem, from labelling on alcoholic beverages (agree) to weight surgery lowering the risk of diabetes (interesting, but not a very fallible nor complex discovery), contrasting starkly the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, I've been thinking about the exclusivity of our idea of 'first world problems' in terms of health in relation to affluence. Just as when one pictures poverty an image of a deprived African featured in an advert inevitably comes to mind, so an image of an affluent American or Briton hunched over a McDonald's burger forms when one pictures obesity. Both, unlike the link between a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and weight loss, rather fallible clichés. The juxtaposition between obesity in the UK and Ebola in West Africa perfectly illustrates this conflict between our pre-conceptions and reality; it is inevitable that one draws the conclusion from these subjects that obesity is physical evidence of affluence and greed (the UK is a more economically developed country, with a high standard of living and quality of life - besides, excess is what causes obesity right?), and infectious, communicable diseases things of the dark ages only suffered by those living in poor, less economically developed countries (Ebola is after all prevalent in West African countries with low GDPs and sparse infrastructural health and education facilities). It is such an exclusive, narrow-minded ideological attitude to conclude these links. In the August 2014 National Geographic magazine, Tracie McMillan explores obesity in relation to affluence in her article, 'The New Face of Hunger', indirectly challenging such conceptions; she focuses on American families and the growing parallel between hunger and obesity (yes, you read that right; hunger and obesity are increasingly linked to one another). The gist of the article is an exploration of 'why [...] people are malnourished in the richest country on Earth' with growing evidence of obesity not in areas of total affluence, but rather poorer ones; hungry ones. It cites the rising trend of 'food deserts' such as the Bronx borough (37% hunger rate) of NYC where fast-food restaurants and outlets are densely situated but grocery stores sparse; the growing dependence upon food banks and stamps (SNAP); and the apparently conflicting reality of homes filled with 'the toys and trappings of a middle-class life' but reliant on donated, 'typically processed', foods to feed them. To borrow a cliché saying actually applicable in truth here - it is so eye-opening. Read it.

"Nearly 60% of food-insecure US households have at least one working family member"

- Tracy McMillan

The reality is, with globalisation and urbanisation, access to TNC food outlets and processed fast food itself has risen dramatically on an international scale and hence as such food is 'plentiful' and 'often cheap' (certainly more so than organic foods), hunger is linked to obesity. Just think - have you ever been somewhere where you couldn't easily (or at least eventually) locate a McDonald's restaurant? Junk food is everywhere and because of its success, it's cheap. Going back to the aforementioned exclusive ideology of links, it wouldn't be wrong to link (in many cases) low levels of affluence with less access to services, commodities and facilities. With less money (or even the same amount of money) and growing food prices (bar junk food, which, inevitably, is on the whole arguably comparatively falling), people cannot afford to eat healthily and hence with reliance upon fast/processed foods, obesity is where their bodies end up. Also linked to growing obesity in areas of poor affluence is the time spent working and trying to earn a living; in many cases (particularly in less economically developed countries), primary income jobs such as manufacturing require longer hours for poorer pay. With less time to shop or exercise, obesity prevails as fast food is easy to acquire (its name speaks volumes -

fast food) and people are unable to schedule time to partake in the minimum requirement of exercise [see

this article published by BBC news yesterday]. People of greater affluence have more access to both healthier food and time for exercise/food preparation/food acquirement/food planning, therefore are objectively less prone to obesity - I say objectively because subjectively, were one to take into consideration the differing backgrounds of people with a range of potential factors affecting their lifestyle, it wouldn't be so straight-forward a link. As McMillan argues, obesity is rapidly becoming the new face of hunger.

Thought #3: China

On track to becoming the 21st century global superpower, China is a source of endless marvel, curiosity and challenge. Interestingly, in his book

'Africa', Richard Dowden notes that were one to look back to the early 20th century, some African countries were marginally ahead of China/India economically in some measures; now, the stark opposite is true. Why did China so successfully develop into the powerhouse it now is, and not African countries? More specifically, how? What was it that enabled such progression? The referenced articles centre around China's socio-political composition and their intentions for the future. In the latter article, Carrie Gracie writes; 'Can a 21st Century China, a global power with a mobile and connected citizenry, find the answers to the challenges of its future by closing down discussion and uniting around the playbook from its past?' Drawing on her question (and based exclusively on these articles), the prospect of the socio-political structure of China being a predominant factor in the nation's dominance grows apparent. China does not comply with the Western moulds for political democracy and relaxed societal constitutions; it is unique and has nearly always been 'on a different path'. Is this uniqueness, this lack of conformity, what is enabling China to develop so superiorly and dramatically, steadying itself to leap ahead of classic world-leading nations? I think it may be a large contributing factor, though as Carrie points out, could potentially have some social and perhaps environmental implications limiting the sustainability of their rate of progress.

Thought #4: Stephen Hawking

"Intelligence is the ability to adapt to change." - Stephen Hawking

I found this quote whilst fuelling my growing anticipation for the release of 'The Theory of Everything' by searching quotes and stills on Pinterest, and was so struck by it that I began to sub-consciously analyse and interpret it (surely we've established by now that my mind works rather weirdly?). It reminded me of one of my earlier posts,

'What constitutes/validates intellect?', and re-engaged me with the subject. I am a firm believer that intelligence stretches beyond memorisation of facts and acceptance of the known; that it manifests itself in challenge of the norm, in exploration of reality, and in creation. It is not stagnant nor inherited (i.e. learnt); it is ever-evolving and developing. I cannot think of anything more exciting nor fascinating than constructions borne of the mind; reading texts such as 'The Night Circus' by Erin Morgenstern or 'Guns, Germs and Steel' by Jared Diamond, or seeing creative movies such as the work of Wes Anderson, or exploring theoretical findings such as by Hawking himself leave me in awe of intellect. It's pretty amazing, when you think of it.

Thought #5: An extension of reality

Imagination. If not reality, then what is it? False? But it is based upon experienced and acknowledged realities; it formulates itself often in pretence of true existence. Think Deja Vu; think the conversations you have in your head; think the scenarios you envision in moments of physical stillness, in those moments before you fall asleep or as you stare out of the window, eyes lulled into a blur. Obviously it's not true. Obviously it's not reality itself. But it's not entirely false either; perhaps, imagination is quite simply an extension of reality; a mental existence.

Until next time (which shall hopefully be less random and sporadically written),

C